Hamlet and Notices to Appear: the impact of the U.S Supreme court's last decision on Immigrants

“Be thou assured, if words be made of breath,

And breath of life, I have no life to breath

What thou hast said to me.”

William Shakespeare,

Hamlet

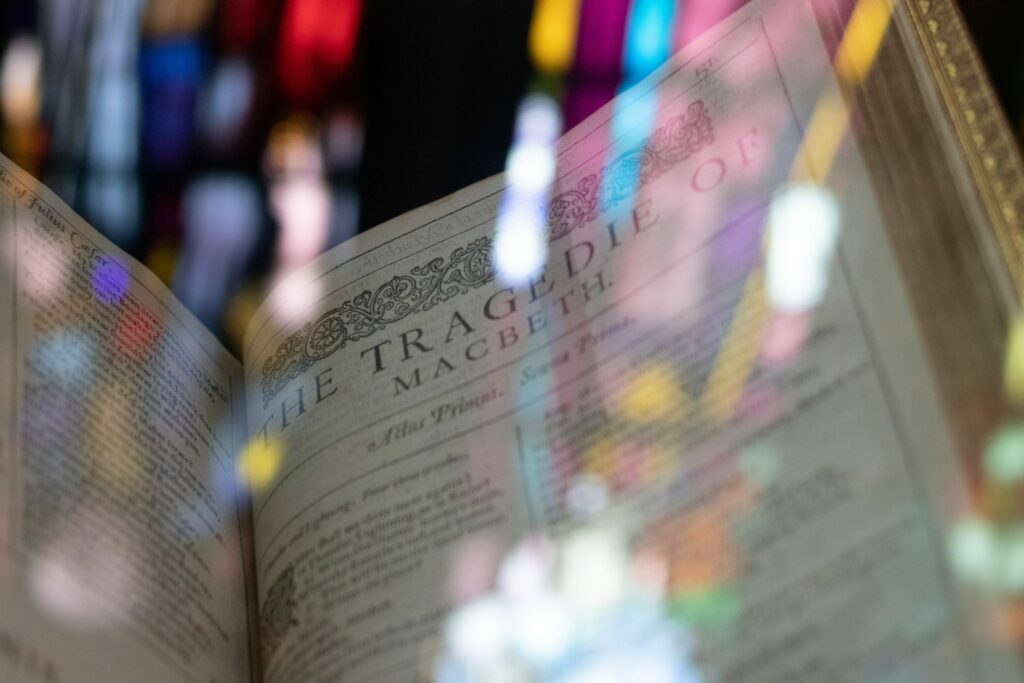

I majored in English Literature as an undergraduate at UNLV. I was and remain a book nerd and lover of linguistic constructions. When I read the above passage from Hamlet many years ago, I found it to be a profound reflection on the world we are capable of creating with words and the life we breath into words as well. Words are powerful. This week, the U.S. Supreme Court thought so too.

In Niz-Chavez v. Garland, 593 U.S. _ (2021) the Supreme Court found it necessary to contemplate the definition of the word “a” in the phrase “a notice to appear” as found in the Immigration and Nationality Act (“the Act”). 8 USC 1229(b)(d)(1) and 8 USC 1229(a)(1). A notice to appear, or an NTA, is the document that begins deportation proceedings against an individual. It is akin to a complaint in a civil case or an information in a criminal proceeding.

The issue at hand in Niz-Chavez is this: does an NTA that is issued incompletely (without a time or place as to when the person must appear in court), but later cured by another NTA with that same information, constitute an NTA for purposes of the “stop-time rule” in cancellation of removal cases? Cancellation of removal is a type of defense to deportation designed to prevent the deportation of someone who has been in the U.S. continuously for ten years, has shown good moral character, and can show that their deportation would cause exceptional and extremely unusual hardship to a spouse, parent, or child who is a U.S. citizen or Legal Permanent Resident.

The Supreme Court’s opinion, authored by Justice Gorsuch, takes up the existential question of when an NTA is really an NTA in this cancellation of removal context. For those Hamlet fans: imagine Hamlet in the infamous “to be or not to be” scene in Act 3 of the play. But I digress. The majority opinion takes us on a grammar-laden journey in considering the meaning of the indefinite article “a”. It does so to determine whether it makes sense to hold that multiple documents, issued serially with different pieces of information, constitute “a notice” OR whether “a notice” must contain all information as required by the Act in one document. The Court concluded the latter. In arriving at this conclusion, the Court wrote these passages, which I found quite amusing:

In response to the [Trump] Government’s arguments made last November that it is “hard” to fill out forms (I’m paraphrasing the government’s argument, of course), the Court wrote: “If the government finds filling out forms a chore, it has good company. The world is awash in forms, and rarely do agencies afford individuals the same latitude in completing them that the government seeks for itself today.” Id. at 13.

- “Just consider the alternative. On the government’saccount, it would be free to send a person who is not from this country — someone who may be unfamiliar with English and the habits of American bureaucracies — a series of letters. These might trail in over the course of weeks, months, maybe years, each containing a new morsel of vital information. All of which the individual alien would have to save and compile in order to prepare for a removal hearing.” Id. at 14.

- “At one level, today’s dispute may seem semantic, focused on a single word, a small one at that. But words are how the law constrains power. In this case, the law’s terms ensure that, when the federal government seeks a procedural advantage against an individual, it will at least supply him with a single and reasonably comprehensive statement of the nature of the proceedings against him. If men must turn square corners when they deal with the government, it cannot be too much to expect the government to turn square corners when it deals with them.” Id. at16.

I felt moved to write about this opinion for two reasons. First, I was tickled at the almost facetious approach the Supreme Court took in examining with a fine-toothed comb the meaning of a minimal word – “a” and the incredible power it wields in legal construction.

For someone like me, who enjoys the black and white of certain aspects of literalism, this opinion was a fun read. Thanks to the presence of this singular-letter word in the Act, the Supreme Court held that the government must play by its own rules and it must play fairly.

Second, because of this “a”, the government has been reminded that an NTA is a solemn document and the people to whom it is issued, should be treated fairly so as to be given sufficient notice to defend themselves from a potentially earth-shattering legal outcome – expulsion from the United States, and very likely, their families. With Niz-Chavez v. Garland, the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed yesterday, immigration proceedings affect an individual’s life, liberty and rights just as much as a criminal proceeding or civil lawsuit – thus, all people, including immigrants, should get a fair shot to defend themselves in their day in court by being put on proper notice.

Sincerely,

Jocelyn Cortez